At the end of March (yes, it’s taken me a month to get around to blogging about it), I visited Savannah, Georgia. When family or friends asked, I said I had always kind of wanted to go to Savannah (it’s supposed to be so pretty!) and I had a travel voucher (because American Airlines screwed up a connection for me last May). I said that because I don’t talk much about my writing (at least not in person, even with family and friends). The most fundamental reason I wanted to go? I wrote a novel set on the Sea Islands of Georgia. The timing couldn’t have been better (but that is a story for another time). The novel was completed years ago (it’s undergone several revisions since then), and I’d always wanted to visit the place that inspired my trip, but I kept putting it off. I finally got my ass into gear. I booked my plane ticket and hotel room, bought a guide book, and plotted out the high points of a relatively brief trip.

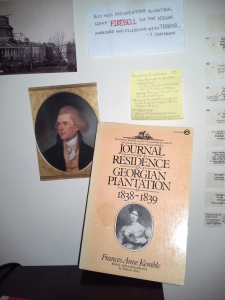

First, I should back up a bit and mention how I came to be interested in the Georgia Sea Islands. I’ve always been interested in the Civil War. (I can’t imagine that anyone with a love of American History is NOT interested in the Civil War.) When I was in elementary and middle school, I started Dear America-style stories about the Civil War. I never got far. I started writing about different periods and for a while was pretty sure I wouldn’t ever seriously consider writing about the Civil War. But a lot of influences from my youth converged to make it inevitable, and when I ran across Fanny Kemble’s Journal of a Residence on a Georgian Plantation (actually a series of “letters sent to a friend”; here is a nice write-up from PBS, here is a link to it on Amazon, and here it is on Project Gutenberg), the cogs in my head started turning.

Fanny Kemble was an English actress born in 1809. Her family was a well-known acting family. At that time, acting was not a very well-regarded profession. Many people saw theatergoing as sinful and actors and (especially) actresses as especially immoral. Women who acted were little more than whores—or were simply whores, in the eyes of many. By the time Fanny took the stage, however, as a young lady trying to help keep her family afloat, these attitudes towards the theater were loosening. Fanny and her family were respected and were for the most part Shakespearean. Acting and the running of theaters was a notoriously precarious business venture. Fanny’s family had run into financial trouble, but Fanny became a sensation almost as soon as she took the stage. She and her father came to America to tour, and it was there (in Philadelphia) that Fanny met Pierce Butler, part owner of several rice plantations on the Georgia Coast.

Although it seems odd to us today, it appears that Fanny wasn’t aware of where her husband’s wealth came from before she married him. In part, this may be because the family were absentee and spent most their time in Pennsylvania and were even active in Pennsylvania politics. Partly, this is because it was considered very impolite to speak about money.

In any case, after years of cajoling, Pierce Butler finally allowed Fanny to come to Georgia with their two children, and thence Journal of a Residence. It is a beautifully written, compelling look at slavery. Fanny’s views and opinions are sometimes startlingly modern (most people wouldn’t expect a Victorian to be so forthright in her support of gender and racial equality).The way she describes Georgia also captivated me. It was clear she wished she could separate the beauty of Georgia from the darkness of slavery. But since she couldn’t, she returned to Philadelphia after several months in Georgia. She divorced Pierce Butler in 1849; the slaves were almost all sold off at auction in 1859 due to Pierce’s fiscal mismanagement; and during the Civil War, the Sea Islands of Georgia fell early to Union occupation. (For the better, let me be clear; the slaves were all freed.)

I won’t burden the readers with a description of my own fictional characters. Suffice it to say that Fanny was the starting point for them, and it was their fictional story (as well as Fanny Kemble’s real-life story) that inspired me to make the journey from DC to Georgia.

I wasn’t just there to see Butler Island, the scene of most of Fanny’s diary. I was also there to experience the city of Savannah. My plan was to spend one day south at Butler Island and the nearby Hofwyl-Broadfield Plantation, then spend the other two full days exploring Savannah.

It was the end of March, but even the end of March is usually very temperate in Savannah. However, it was an especially cold snap; back home, temperatures barely rose about freezing. In Savannah, it was sunny and about sixty degrees. Not balmy, but definitely doable.

My first full day was almost surreally bright and clear. The sky was a fantastical kind of blue, and everything seemed so green when I stepped off the plane. It had been a long, cold winter in DC, and we hadn’t emerged from it yet. There in Savannah, spring was bursting at the seams. I got up early the morning after I arrived, hopped in my rental car, and drove south . . . along I-95. Yeah, it’s hard to escape I-95 on the East Coast. And it’s not exactly a romantic way to get around, but it is efficient. And it was such a beautiful day, and the drive was so lovely, that I didn’t even mind I was on an uninspiring 20th century highway.

It took about an hour to get to Butler Island. To get to the island, you get off I-95 the exit north of it, head slightly east and then turn south at the town of Darien, which was the closest town to the Butler plantation and which is mentioned multiple times in Fanny Kemble’s memoirs. Today, it’s a quiet little clutch of houses. Later, I would get turned around and find myself driving down enchanting neighborhood roads, only two lanes, no lines, a median of grass and flowering trees down the middle, small houses with bursting plant life all around. It had that pleasant, honeyed Southern charm you hear about—and that you can’t appreciate unless you see it.

Beyond Darien, over two bridges, there is a red chimney sticking up out the exquisitely green grass right by the side of the road. This is what I came to see: this is what’s left of the plantation that Fanny Kemble knew. The chimney is what remains of the steam-powered rice mill at Butler Plantation. There is also the stump-like ruin of the tide-operated mill. Time was, this was a thriving plantation sending flatboats laden with rice down the river to Savannah and further afield. But like everything

Beyond Darien, over two bridges, there is a red chimney sticking up out the exquisitely green grass right by the side of the road. This is what I came to see: this is what’s left of the plantation that Fanny Kemble knew. The chimney is what remains of the steam-powered rice mill at Butler Plantation. There is also the stump-like ruin of the tide-operated mill. Time was, this was a thriving plantation sending flatboats laden with rice down the river to Savannah and further afield. But like everything

associated with slavery, it evaporated after the war. Today, it’s just these remnants. The pretty white house standing behind the chimney is twentieth-century; the house that Fanny stayed in is gone.

It made a striking image: the green, green grass, the brilliant sky, the red bricks , the white house.

By the road and the chimney is a historical marker telling visitors about Fanny’s daughter Frances, who came back to Butler Plantation after the war and tried to resurrect it, and about Owen Wister, who was Fanny’s grandson by her other daughter, Sarah. Oddly enough, Fanny herself isn’t mentioned, perhaps a pointed omission (who says the Civil War ended 150 years ago?).

After taking entirely too many pictures (and many selfies), I started walking around. The remains of Butler Plantation are part of a wildlife refuge, so it has very much gone back to nature. I quite merrily walked along the paths, among hedges of jasmine just like the jasmine Fanny described in her memoirs. Ducks floated on the pond. Bees buzzed. There was no one there but me. I felt very much a part of this place. I couldn’t help thinking of the alligators and snakes that Fanny mentioned, and I kept an eye out for where I was stepping . . .

I ate some lunch at a little boat launch near the house, then got back in the car to drive down a dirt road (Champney Road) just to the south of the plantation ruins. The road turns and wanders. A family was fishing in a pond, but otherwise, there was no one near. The road kept going west until it reached I-95. Yeah. I-95 actually cuts right across Butler Island. Considering that, it’s fairly unobtrusive. It glides by overhead, cars and trucks zipping by at 70 miles an hour. The pylons sink into the sandy earth. Otherwise, it doesn’t affect the island—no Mickey D’s, no off-ramps, no guardrails.

You can drive beneath I-95, but on the other side, the sign quite expressly says, “No vehicular traffic.” So I parked and jumped out and stated walking. I didn’t get too far, honestly. It’s a big island, and there’s nothing there except for the remains of dikes and canals. I stood at the beginning of one of these 170-year-old ditches and stared down the length of its regular course, where it disappeared into the vegetation. That’s all there is here, now: straight lines of water, and untended vegetation. I stood there, looking, taking it all in. Just imagine. Before it was a rice plantation, it was a cotton plantation.

I wanted to stay, to explore it for days on end. I wanted to know so much more. But my time was limited, and there was more to do and see.

My next stop was south of Butler Island, at Hofwyl-Broadfield Plantation. Unlike Butler Plantation, which succumbed to the ravages of time, Hofwyl-Broadfield was lovingly preserved by the family who lived there. It was a rice plantation, then a dairy, and then a family home until the last woman to own it died at an old age and left it intact to the state of Georgia. Everything in it came with it: furniture that dated back to the Antebellum period,  farm equipment from every time period, various outbuildings. It is now an exceptional place to visit and learn. The visitors center has a great video about how rice plantations operated and has a wonderful selection of books (I would have bought four or five but had to think about how much space they would take up in my suitcase!). There is a loop for a nature walk, which takes you past the ruins of the tabby-built rice mill and to an overlook of the salt marsh. (It’s incredible how high those grasses are! They’re at least ten feet high, though you wouldn’t expect that from a distance.) I had way too much fun setting up my camera with a timer and taking pictures of myself in the clearing with the ruins of the rice mill. The house tour was informative and immersive—like I said, pretty much all the family possessions from every period remained there in the house. It was a quirky little place, not at all reminiscent of the romantic visions some people have of plantation houses. It was comfortable but not large or grand. Beyond the house, there was a bevy of outbuildings, from the barn to the garage to slave quarters.

farm equipment from every time period, various outbuildings. It is now an exceptional place to visit and learn. The visitors center has a great video about how rice plantations operated and has a wonderful selection of books (I would have bought four or five but had to think about how much space they would take up in my suitcase!). There is a loop for a nature walk, which takes you past the ruins of the tabby-built rice mill and to an overlook of the salt marsh. (It’s incredible how high those grasses are! They’re at least ten feet high, though you wouldn’t expect that from a distance.) I had way too much fun setting up my camera with a timer and taking pictures of myself in the clearing with the ruins of the rice mill. The house tour was informative and immersive—like I said, pretty much all the family possessions from every period remained there in the house. It was a quirky little place, not at all reminiscent of the romantic visions some people have of plantation houses. It was comfortable but not large or grand. Beyond the house, there was a bevy of outbuildings, from the barn to the garage to slave quarters.

But perhaps the very best part of the place—for me!—was the trees. That sounds a little weird. Let me explain. I’m not what you call a huge tree person. My dad can instantly name most any tree you can point to. I can’t. I can tell a beech from a maple from an oak, but that’s about it. I do, however, know what a live oak is. Or at least, I had some conception of it, but until I really saw one of these ancient, magnificent beauties there at Hofwyl-Broadfield, I didn’t really understand. The trees there are said to be as old as eight hundred years. They’re massive, dwarfing the house. And what’s more, they aren’t just large and old; they’re also twisted and moss-covered, with their broad boughs like little ecosystems of their own. They’re almost magical. I was so enamored of the way one them leaned to the side, twisted around itself, and then leaned back the way it came, that I took about thirty pictures. It was absolutely beautiful.

Once I’d done the nature walk, toured the house, seen the museum, and gotten a few goodies at the gift shop, it was back in the car to head back for Savannah . . .

And since it occurs to me that I’ve expended a lot of words on one day of travel, I’m going to save the remainder of my trip for another post.