A year ago now, I wrote a post about what I had found out thus far about the old house I grew up in. I have been meaning for ages to continue the story, as I left it on something of a cliffhanger (you know, a cliffhanger as far as historical research goes).

As a refresher, I grew up in an old house in northeastern Maryland that was built sometime in the first part of the 19th century. It was built by the Rogers family, who lived there until 1912. The Rogerses were Quakers, and at one time that section of Maryland was considered (by Pennsylvania) to be part of Chester County, Pennsylvania. I had found out all of this through tracking down the deeds at the county courthouse in Elkton, Maryland. The last item in the records, though, was a strange document from 1823 that was filed as a “decree” and seemed to be part of the settlement of Thomas Rogers’s estate. The trail seemed to run cold there.

Here’s the pertinent part of the “decree”, which is really opaque:

…the balance of the said purchase money [for the sale of some land] is now to be distributed amongst the legatees mentioned in the 20th item in the same will of whom John Rogers the part of the first part is one. And whereas the said John Rogers is also entitled to a small dividend or distribution share upon the general settlement of said Thomas Rogers Sr.’s estate. And whereas by the will of the said Thomas Rogers there is devised to his son John the part of the first part certain lands and tenements mentioned in said will and in the 14th item thereof in fee provided he the said John Rogers should pay the amount of a bond given by him to his father Thomas Rogers for the same lands, and by the codicil to the same will there is devised to the same John Rogers the same land in fee simple with remainder over to his surviving brothers and sisters in case he dies without issue of his body. And whereas the said John Rogers hath agreed and by these presents doth agree to release, transfer, and set over to the other persons mentioned in the 20th part of the same will all his, the said John’s, share or dividend of the balance of the purchase money for which the lands as aforesaid devised to his brother Thomas Rogers [Jr.] hath sold, and also the dividends or distributive share which he may be entitled to upon a general settlement of the estate of the said Thomas Rogers [Sr.], his father, deceased.

Basically, each of the siblings was given a portion of the sale price of certain land, but John both owed money to his father and had inherited some land directly from his father. In sum, he gave up his portion of the estate in order to pay off the debt, and in return he received the land he’d been left by his father.

As I was doing some genealogical research on the Rogerses, I came across a will of one Thomas Rogers—in the Chester County, Pennsylvania records. It was dated 1774 and was fascinating. As it turns out, this document wasn’t what I thought it was (more on that later), but there are some very interesting bits anyway, such as the bit about apprenticeships and the items left to his wife Catherine:

I, Thomas Rogers, of the township of West Nottingham in the county of Chester and Province of Pennsylvania (or so reputed [quite possibly a reference to the dispute between Maryland and Pennsylvania over the border]), being now weak of body but of sound mind and perfect memory, do make this, my last will and testament—thereby disposing of the worldly goods and estate it hath pleased God to bless me with in [the] manner following—viz:

First, my will is that my body be decently buried at the discretion of my executors hereafter named, and my just debts and funeral expenses defrayed as speedily as possible after my decease.

Secondly, I give and bequeath unto Catherine, my loving and well-beloved wife, the third part of my plantation I now live on while she remains my widow [i.e. only if she doesn’t remarry] and the east end [eastern?] or newest house to live in, with free egress and regress to and from the same with privilege of water and firewood.

Thirdly, I give and bequeath to her my said wife the third part of my personal estate after my debts and funeral expenses are paid, and also her riding mare and saddle, one bed and bedding.

…

Ninthly, my will is that the share that shall fall to my said son Thomas on a division of the land be rented, and also the residue of my personal estate after my debts and legacies are paid as above said, be applied to the schooling and maintaining [of] my two youngest children until they shall arrive to [the] age to be put apprentice, and no charge to be brought against them out of the money left them for their maintenance.

Tenthly, as there is [not?] a burying ground on my said plantation, my will is that one quarter of an acre be reserved for that use forever, and provided as of one perch [i.e. 16.5 feet] wide to the Great Road, South [and?] of the same to it and from it. [?]

Naturally, the bolded part got my attention. Excuse me, but did you say “burying ground”? Good Lord, where?!

The sad truth is that we’ll probably never know exactly where, but this much is clear upon closer inspection: this is NOT the Thomas Rogers I was looking for (to, uh, paraphrase Star Wars). As it turns out, there were several Thomas Rogers in the family. The Thomas Rogers I want (the guy who died and left his son John our land) was born in 1738, and this doesn’t fit with the will above (he would not have been old and infirm, as this will indicates in its opening lines). Also, the children listed in the will do not match with the children of the Thomas I want. As it turns out, our Thomas’s grandfather was another Thomas born in 1690, making him 82 when this will was made (meaning “old and infirm” would fit). Our Thomas’s great-grandfather was another Thomas born 1665 in England. So this will belonged to the Thomas born in 1690 and does NOT refer to the land our house stands on.

I pursued a few more avenues for figuring out the answers to my big questions: I decided to look into the Nottingham Lots, which was an area of land sold off way back when the Penns still claimed that section of Maryland as their own. This was 1712, and our land is very near the sight of the Lots. I was having all kinds of trouble figuring out whether our house sat within the bounds of the Lots or not, because I wasn’t able to line up the Lots precisely with a current-day map. I visited the Historical Society of Cecil County, perused a book called The Nottingham Lots: A Tercentenary Celebration (2001), and looked at some books in the local library about the Quakers. I compared maps; I looked into land patents at the Maryland State Archives; I came closer to my goals but never quite found the answers I wanted.

What I found were records for the patenting of several plots of land by various Rogers family members in the late 1700s. The problem again was not being able to line up what I found precisely with current geography. I found Rogers’ Rest (patented 1789 by William Rogers and too far north to be our land), Pleasant Seat (patented 1789 by William Rogers and an early candidate that upon closer inspection is too far west to be our land), Pleasant Farm (patented in 1790 to Elisha Rogers and also too far west). Springton (patented 1790 by Thomas Rogers) was in very nearly the right location but was clearly too small to be a possibility. Then there was Rogers’ Range (patented 1790 by Thomas Rogers), which seemed to be in exactly the right place due to the creek (North East Creek) and mill noted in the patent. But it was shaped oddly, like a backwards C: two rectangles of land were connected by a very slim strip of land running north to south. Most frustrating of all, the blank center of this “c” shape seemed to be exactly where our house stands today. The map in the patent notes this is “Thomas Rogers’s other land, patented”, but I could not find the patent for that land.

However, digging through some documents at the Historical Society, I found a notation on a map saying the land was called “Providence” and was “unpatented”. And I was able to find the document for “New Providence”, an unpatented bit of land. Now, this appears to be the right place and the right time and the right person (Thomas Rogers, 1774), but because it was unpatented, it didn’t have the detail found in the patented document, such as roads or the name of neighboring lots. Still, it appears to be correct.

Which would put our land directly off the southeastern edge of the Nottingham Lots, as in adjacent to it but not part of it.

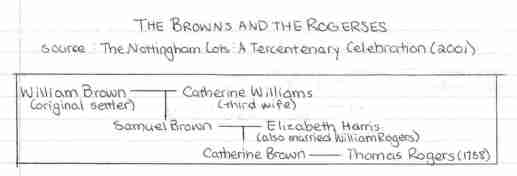

This was disappointing, because in my research on the Nottingham Lots, I found a surprising level of connection between the Rogerses and the Browns, who were some of the original settlers of the Nottingham Lots. According to The Nottingham Lots: A Tercentenary, James and William Brown were brothers who came over from England when the area was still very much a frontier. They bought several lots and settled in “East Nottingham”. The pertinent part is that William bought one of the southeastern lots, remarkably close to where our house now stands. And, as it turns out, his granddaughter Catherine Brown married our Thomas Rogers (b. 1738). What’s more, her mother, Elizabeth Harris Rogers, was Thomas’s stepmother, because she was the second wife of his father William Rogers. In other words, Catherine and Thomas were stepbrother and stepsister. Intriguingly, in The Nottingham Lots: A Tercentenary, it says that the original settler William Brown left the bulk of his estate to his son Samuel, whose daughter is the Catherine who married our Thomas. So, all of these connections suggest the possibility that bits of the Nottingham Lots were passed down from William Brown to Samuel Brown to Catherine Brown and then to her children by Thomas. And yet . . . it appears this was just a massive red herring.

The real pain is the so-close-but-not-quite-there aspect of it all. I simply can’t place the land patents and the Nottingham Lots precisely on a modern-day map. If I could, I might be able to make more headway!

Another small thing I found while at the historical society was a notation about a mill that was on the North East creek very near our house and was clearly owned by the family: it was called, uninspiringly, “Rogers’ Mill”, listed in 1856 as “clipping the North East Creek” upstream of Warburton Sawmill and having a fall of 15 to 20 feet. There is a cow pasture in that spot now.

I think the moral of the story is that I’ve exhausted the avenues I’ve pursued thus far. What I need to do next is try to locate wills, look at tax record, see what more can be found by visiting the Maryland State Archives, and maybe check out some old newspapers. Since I work full-time and live two hours away now, my research takes place only in fits and starts, but I hope to learn more as time goes by.